My problem with "City Pop"

Ok, so first listen to a bit of each of these songs:

Pink Shadow - Bread & Butter

Barbecue (1974)

Once Upon a Song - Masayoshi Takanaka

The Rainbow Goblins (1977)

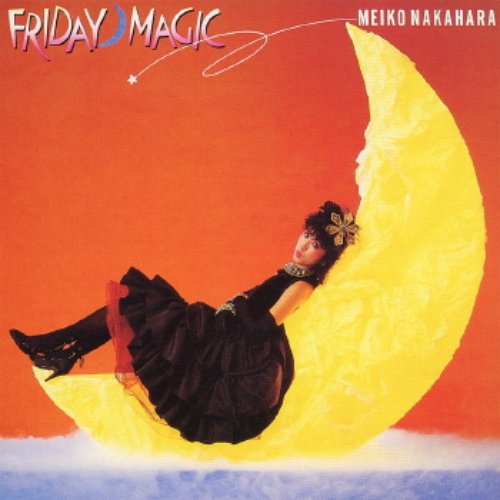

Fantasy - Meiko Nakahara

Friday Magic (1982)

All of these songs are songs that categorized by the popular internet term "city pop." See the problem here? All of these songs are different genres and have a different sound. By calling them all city pop, it's grouping a whole lot of wonderful genres and subgenres together into one mega-genre. I mean, it's not really a huge problem by any means--I use the term yacht rock all the time, and that is also certainly a mega-genre that over time has lost meaning. A broad term like that for Western consumption can be good in some ways, because it's an easy key word to help people discover the music Japan has to offer. I think the issue arises when all the music under the mega-genre is defined by surface level popular songs.

For instance, the big one: Plastic Love by Mariya Takeuchi.

Plastic Love - Mariya Takeuchi

Variety (1984)

Don't get me wrong, this song is great, but it is certainly defining of the mega-genre since it blew up on youtube around the late 2010s. Then compare it to some of the more niche "city pop" stuff, Haruomi Hosono's early solo work for example.

Hurricane Dorothy - Haruomi Hosono

Tropical Dandy (1975)

They sound quite a lot different besides the fact that they're both in Japanese, but I see them both labeled as city pop. I think that when people get the idea that all city pop is like the stuff at the top like Plastic Love, the music that doesn't fit that aesthetic-- but still needs the label to get discovered in the US-- gets buried. The idea of genres is to make it easier to find the music you like, and in the West the main "genre" of Japanese music we talk about is city pop. Again, no hate to the stuff popularized by the term--heck, Tatsuro Yamashita is probably my favorite artist of all time, and he is definitley a front runner of the mega-genre. That said, there's a lot more to Yamashita underneath Ride on Time and Big Wave, especially session and production work, that goes under the radar. We'll definitley be talking a lot more about Yamashita later.

An article by Moritz Sommet talks about this issue and attemps to clear up confusion surrounding the term. To quote Sommet directly:

What defines City Pop most clearly in its cultural context is the absence of any obvious markers of a Japanese musical identity. Other than its mostly Japanese-language lyrics, it usually contains no traces of the musical characteristics that are conventionally thought to be ‘Japanese’ in modern popular music[.]1

This point is highly interesting to me because it actually does begin to clear up what the genre centers around. The lyrics and iconography of Japanese pop music of the 70s and 80s often does magnetize towards the beaches and cities of America (mainly the West coast), but besides this you also see the style of music heavily influenced by pop music in America. But besides Japanese lyrics, it can't be disputed that there is something else going on outside the realm of western influence that is hard to put your finger on. Maybe the most interesting thing I found in Sommet's article is a quote from a 1977 article by music critic Tōno Kiyokazu where he talks about the band Happy End (featuring the above mentioned Haruomi Hosono) and their relation to a then new term: "City music."

I think that just as with the word New Music itself, City Music is nothing more than a "feeling word" and doesn't hold any particularly deep meaning. Should I try defining it for you? Maybe it's something like "New Music that has an urban feeling".2

Even at this point, the idea of "city pop" or in this case "city music" is a vague one, one that can only be described in relation to feelings. Sommet explains that by "new music" Tōno is talking about "a singer/songwriter-based genre that had emerged in the mid- to late 1970s."1 Tōno goes on to speak on how Happy End's album Kazemachi Roman was the first example of "new music" that made him feel "all the nuances of the city."

Kaze Wo Atsumete - Happy End

Kazemachi Roman (1971)

I found this espeically interesting because the album Kazemachi Roman is an album I would consider to be unfortunately less exposed in the 2010s city pop boom. As Sommet says, the folky album "has few similarities with the glitzy, beach-adjacent transnational metropolis of 1980s City Pop."1 However, being a pioneer of this music, it gets burried towards the middle of the city pop food chain.

At this point, I've been on this tangent for a bit too long so I will close by saying something that I feel encompasses what I got out of my research: city pop is a good feeling word, not a good genre word. There is no doubt that there is music that brings a nostalgic feeling of city and beach life that is described well by the term, but because of its trendiness the term has been broadened to the point of meaninglessness as a genre. However, much like yacht rock, I get that it can be used to find more of the music you like, especially when you're limited by the language barrier. That's all I've got to say on the subject in this post, but we will definitely be coming back to these ideas and Sommet's paper in the future (as well as other papers). I also want to touch on remixes, AMVs, and other stuff that contributes to the aestheticization of Japanese music, but again I don't want this to run on for too long. See you later!